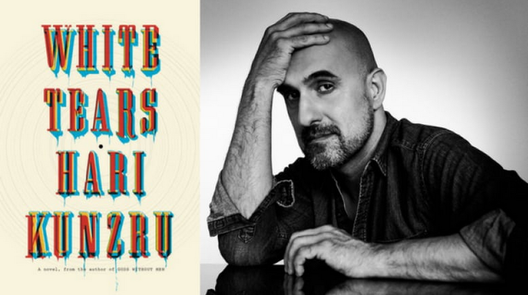

How Hari Kunzru’s excavation blues music resulted in a supernatural novel about America’s racial history

Originally appeared in Google Play Books (now Defunct)

In his fifth novel, White Tears, Hari Kunzru tells the story of two white audiophiles, Seth and Carter, living in New York. They surreptitiously record a man singing a blues riff in a park and manipulate the recording to sound like a 1928 studio session. After they post the song online, tragedy befalls Carter and Seth undertakes a desperate trip to the South to try to make amends for their act of cultural theft. His story crosses paths with and becomes hopelessly entangled in the troubling racial history of the United States. I spoke with Kunzru about how his love of the blues informed this novel, what troubles him about hipster culture, and why he chose the genre of the ghost story to explore America’s racial past.

What was the inspiration for White Tears?

I moved to the United States from England in 2008, just in time for Obama’s election. People were saying, “We have a black president now. We are in post-racial America, and we don’t have to think about race any more.” Now what is happening is the reverse: We are in a time of intense racial antagonism. I’ve been quite shocked. I thought I understood American history and culture well enough to have a handle on how race plays out here, but I really didn’t. It’s so much more toxic than I realized. This is a country that is haunted by its racial history. So a ghost story seemed like a perfect form to approach that. It all clicked together when I linked my interest in crackly old blues records to a contemporary story about race.

There is a spectral figure in the novel, but at times I’m not sure if he is a ghost or a product of the protagonist’s imagination.

I wanted to write something that was propulsive and entertaining because I was dealing with dark political material. But I did struggle with how supernatural I wanted the book to be. I’m drawn to ambiguity, so I made it possible to read the book as if there is no ghost at all and Seth is just having a breakdown.

I want the reader to ask: Is Seth’s guilt producing these visions of a ghost? Is he a liberal who has been driven crazy by his own intense guilt and feelings that he has to be a white savoir on behalf of black people? I really wanted this book to exist in a gray, uncanny, uncomfortable area where all these things were floating around without being resolved. This is a book that wants to take people into the unsayable things about history. There are no easy answers, or even easy questions.

“White Tears” is a phrase used to describe when white people get upset at non-existent racial injustice against them. Why did you choose that title?

It’s a phrase that turns up in the most heated contexts on the Internet. It’s about whose pain is justified and whose pain should be censored. Those are questions that the book deals with. It’s also a contemporary title. I didn’t want to give the book a “ye olde blues-y” title, because it’s about something contemporary. For example, I was thinking about contemporary hipster culture and that wish to dress up in the coolness of a black outsider without paying the cost. It’s not an innocent wish, that fantasy of the suburban white kid of having the cool or the street authority of the urban black kid. That cultural stuff is connected to really material stuff like who is being exploited and who is being paid. I wanted to connect contemporary cultural ideas with a history of racial exploitation.

One of my favorite scenes is one set in 1964. In this scene, a white collector castigates a black crowd for listening to a jukebox: “Forget this plastic trash. Pick up a fife! A fiddle! Blow over a damn jug!” You seem to be getting at something here about the nexus of cultural appropriation, nostalgia, and racism. What were you thinking about in that scene?

In American culture, the blues is a cipher for authenticity. It turns up in beer commercials as the rugged music of gritty real America. This contemporary view of the blues has been filtered through a history of collecting culture that started after World War II. These northern white male collectors would go door-to-door in Southern black neighborhoods trying to buy records, during the same time that Civil Rights workers were going door-to-door trying to get people to register to vote.

They really did feel the jukebox was destroying the music they wanted to preserve. They were attracted to a sense of the authentic primitive, but that idea didn’t represent what was happening. Robert Johnson sings, “Bury my body down by the highway side, so my old evil spirit can get on a Greyhound bus and ride.” This lyric is all about motion, which is very modern. He was someone who traveled, no someone who was stuck in the Mississippi Delta. The idea of the primitive also obscures the fact that these musicians were very sophisticated. They had a wide repertoire. They played blues, gospel, or, if they had a white audience, polka. These white collectors wanted to keep people in a prison of authenticity, rather than accepting that culture changes and people might want to listen to R&B on a jukebox.

Confronting and interrogating history seems to be at the core of your work. How do you engage with history in your novels?

I don’t want to use history as a decorative device to make something feel luxurious or alien. I want to use history to help me talk about what is urgent and present. I’m a library nerd, I love tracking down these stories. I always find that the more I excavate something, the more weird and complicated it gets. It’s always true that reality is so much stranger than fiction or more strangely shaped than fiction. The simple version of things is always complicated by finding out what actual happened.

You already know a lot about blues music and record collecting before you started writing White Tears. Did you have to do additional research?

I took road trips to Mississippi and looked for landmarks mentioned in blues lyrics or in the mythology surrounding the blues. It’s really interesting because there is an absence there. The thing you have come to see is not actually there. There’s a myth that Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil in exchange for guitar skills. There are various signs in various places saying this is definitely the place where Johnson sold his soul.

When I go to these places I don’t expect to have a revelation about the actual place. Instead something incidental happens or I see some detail that will find its way into the book. One time, I was sloshing about in a graveyard after a heavy rainfall looking for Johnson’s grave. It was an intense experience. I was ankle deep in mud looking for this marker saying that is the definitive place where Johnson is buried, while knowing that there are two other places making the same claim.

White Tears moves between time periods and geographical locations. How did you approach structuring this novel?

I wanted to pull off the trick of dissolving time. As the book progresses, time collapses. The past and present are simultaneous. At one point in the book, a character mentions that the inventor Guglielmo Marconi thought that sound waves never really die away, they just become fainter and fainter. Marconi said if you got the right equipment, you could pick up the Sermon on the Mount. I like the idea that nothing is ever really gone.

A moment in which time seems to stop entirely is when one of the characters hears “The Laughing Song.” The book has two pages of text that just says “ha ha ha” over and over again. How do you want the reader to encounter those pages?

The genre of the laughing song comes from the 19th-century. These songs start with a black performer singing about the racist things white people say when they see them. Then the song dissolves into rhythmic laughing. It’s the laughter of somebody who is trying to diffuse a potentially violent situation. There is such a horror to the laughter. The laughter is a window into what it felt like to be a black man on the street at sun down in the south during segregation.

I specified to the publisher that I wanted it to run as spread so that the reader turns the page and has “ha ha ha” on the left and right side. To me that is the heart of darkness, or the heart of whiteness, in the book. It’s the kind of horror that can’t be described and just exists in this contentious laughter.

What was the inspiration for White Tears?

I moved to the United States from England in 2008, just in time for Obama’s election. People were saying, “We have a black president now. We are in post-racial America, and we don’t have to think about race any more.” Now what is happening is the reverse: We are in a time of intense racial antagonism. I’ve been quite shocked. I thought I understood American history and culture well enough to have a handle on how race plays out here, but I really didn’t. It’s so much more toxic than I realized. This is a country that is haunted by its racial history. So a ghost story seemed like a perfect form to approach that. It all clicked together when I linked my interest in crackly old blues records to a contemporary story about race.

There is a spectral figure in the novel, but at times I’m not sure if he is a ghost or a product of the protagonist’s imagination.

I wanted to write something that was propulsive and entertaining because I was dealing with dark political material. But I did struggle with how supernatural I wanted the book to be. I’m drawn to ambiguity, so I made it possible to read the book as if there is no ghost at all and Seth is just having a breakdown.

I want the reader to ask: Is Seth’s guilt producing these visions of a ghost? Is he a liberal who has been driven crazy by his own intense guilt and feelings that he has to be a white savoir on behalf of black people? I really wanted this book to exist in a gray, uncanny, uncomfortable area where all these things were floating around without being resolved. This is a book that wants to take people into the unsayable things about history. There are no easy answers, or even easy questions.

“White Tears” is a phrase used to describe when white people get upset at non-existent racial injustice against them. Why did you choose that title?

It’s a phrase that turns up in the most heated contexts on the Internet. It’s about whose pain is justified and whose pain should be censored. Those are questions that the book deals with. It’s also a contemporary title. I didn’t want to give the book a “ye olde blues-y” title, because it’s about something contemporary. For example, I was thinking about contemporary hipster culture and that wish to dress up in the coolness of a black outsider without paying the cost. It’s not an innocent wish, that fantasy of the suburban white kid of having the cool or the street authority of the urban black kid. That cultural stuff is connected to really material stuff like who is being exploited and who is being paid. I wanted to connect contemporary cultural ideas with a history of racial exploitation.

One of my favorite scenes is one set in 1964. In this scene, a white collector castigates a black crowd for listening to a jukebox: “Forget this plastic trash. Pick up a fife! A fiddle! Blow over a damn jug!” You seem to be getting at something here about the nexus of cultural appropriation, nostalgia, and racism. What were you thinking about in that scene?

In American culture, the blues is a cipher for authenticity. It turns up in beer commercials as the rugged music of gritty real America. This contemporary view of the blues has been filtered through a history of collecting culture that started after World War II. These northern white male collectors would go door-to-door in Southern black neighborhoods trying to buy records, during the same time that Civil Rights workers were going door-to-door trying to get people to register to vote.

They really did feel the jukebox was destroying the music they wanted to preserve. They were attracted to a sense of the authentic primitive, but that idea didn’t represent what was happening. Robert Johnson sings, “Bury my body down by the highway side, so my old evil spirit can get on a Greyhound bus and ride.” This lyric is all about motion, which is very modern. He was someone who traveled, no someone who was stuck in the Mississippi Delta. The idea of the primitive also obscures the fact that these musicians were very sophisticated. They had a wide repertoire. They played blues, gospel, or, if they had a white audience, polka. These white collectors wanted to keep people in a prison of authenticity, rather than accepting that culture changes and people might want to listen to R&B on a jukebox.

Confronting and interrogating history seems to be at the core of your work. How do you engage with history in your novels?

I don’t want to use history as a decorative device to make something feel luxurious or alien. I want to use history to help me talk about what is urgent and present. I’m a library nerd, I love tracking down these stories. I always find that the more I excavate something, the more weird and complicated it gets. It’s always true that reality is so much stranger than fiction or more strangely shaped than fiction. The simple version of things is always complicated by finding out what actual happened.

You already know a lot about blues music and record collecting before you started writing White Tears. Did you have to do additional research?

I took road trips to Mississippi and looked for landmarks mentioned in blues lyrics or in the mythology surrounding the blues. It’s really interesting because there is an absence there. The thing you have come to see is not actually there. There’s a myth that Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil in exchange for guitar skills. There are various signs in various places saying this is definitely the place where Johnson sold his soul.

When I go to these places I don’t expect to have a revelation about the actual place. Instead something incidental happens or I see some detail that will find its way into the book. One time, I was sloshing about in a graveyard after a heavy rainfall looking for Johnson’s grave. It was an intense experience. I was ankle deep in mud looking for this marker saying that is the definitive place where Johnson is buried, while knowing that there are two other places making the same claim.

White Tears moves between time periods and geographical locations. How did you approach structuring this novel?

I wanted to pull off the trick of dissolving time. As the book progresses, time collapses. The past and present are simultaneous. At one point in the book, a character mentions that the inventor Guglielmo Marconi thought that sound waves never really die away, they just become fainter and fainter. Marconi said if you got the right equipment, you could pick up the Sermon on the Mount. I like the idea that nothing is ever really gone.

A moment in which time seems to stop entirely is when one of the characters hears “The Laughing Song.” The book has two pages of text that just says “ha ha ha” over and over again. How do you want the reader to encounter those pages?

The genre of the laughing song comes from the 19th-century. These songs start with a black performer singing about the racist things white people say when they see them. Then the song dissolves into rhythmic laughing. It’s the laughter of somebody who is trying to diffuse a potentially violent situation. There is such a horror to the laughter. The laughter is a window into what it felt like to be a black man on the street at sun down in the south during segregation.

I specified to the publisher that I wanted it to run as spread so that the reader turns the page and has “ha ha ha” on the left and right side. To me that is the heart of darkness, or the heart of whiteness, in the book. It’s the kind of horror that can’t be described and just exists in this contentious laughter.