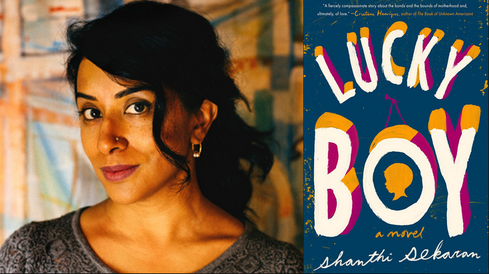

How Shanthi Sekaran learned how to dig deep and get into character’s minds to tell a complex tale of family, immigration, and belonging in Lucky Boy

Originally appeared in Google Play Books (now defunct)

Shanthi Sekaran’s second novel, Lucky Boy, tells the story of two women who love and care for the same child. The boy’s biological mother Soli is an undocumented immigrant awaiting deportation in a detention facility and fighting to take her son with her. Kavya fosters him after Soli is arrested and hopes to adopt him permanently. The book offers no easy answers. Instead, it is a moving meditation on immigration, family, and belonging. In a starred review, Kirkus Reviews called it a “superbly crafted and engrossing novel.” I spoke with Sekaran about creating nuanced characters, the inspiration for her novel, and what she hopes readers can learn about generosity from Lucky Boy.

What was the inspiration for Lucky Boy?

I heard a news story about a Guatemalan woman battling for her son. She was in detention and waiting to be deported. An American couple had been caring for her son while she was incarcerated and wanted to adopt him. I really wanted to know what was going on in these people's minds. What was the biological mother going through? What was the adoptive couple telling themselves? What stage of love had they gotten to that they could justify adopting another woman's child?

In your book, the foster parents are the children of immigrants. Their parents came to the United States legally from India. Why was it important to the story that the foster parents be Indian American?

I am the daughter of immigrants, so writing about Indian Americans is the truest expression of myself. I've always been aware of disparities between groups of immigrants. The difference is that documented immigrants have a visa, which is a privilege, psychologically and legally. But undocumented immigrants have the same hopes, ambitions, and needs as documented immigrants.

I was able to explore those differences because I made Kavya and her husband Indian American. By having the foster couple be Indian American, it makes it clear that this book isn’t about Mexicans versus white people. It’s a book about the different experiences of immigrants.

Was it a challenge to write the character of Soli, whose cultural background and life experience is so different than your own?

That was pretty daunting. I started with research to get a sense of the statistics related to undocumented immigrants in detention. Then I started writing from her point-of-view to force myself to plunge into her experience completely. I eventually switched to the third person, but I used the first person initially to discover where we connected and where we diverged. I will never be her. I will never truly know what it is like to be undocumented. However, there are connections between the two of us: living in Berkeley, being a woman, being a mother—motherhood was a big connection.

My main goal was to present Soli simply as a human being. She is a woman who has hopes for herself and for her little boy. She wants to establish a life for herself, a way to function, work, and be okay. When people start seeing undocumented immigrants as humans, just like any 4th- of 5th- generation American, it becomes harder to see them as criminals and interlopers and easier to see that maybe they do deserve a chance here.

There are some pretty harrowing moments with Soli inside detention facilities. How did you write those scenes?

Again, I started with research. I researched into the detention system so I would know realistically what does and doesn't happen inside those facilities. I learned the very dry step-by-step process an undocumented immigrant goes through from incarceration to deportation. Then I thought a lot about the psychology of incarceration, both from the point of view of people who are imprisoned and those who are in charge. I thought about power dynamics between humans. Then I just tried to engage with the story and tell it in a way that was very spare. I wanted to let the events speak for themselves so that I didn't have to provide commentary on what was happening. The research really empowered me to tell the story that I wanted.

Those scenes are intense, but there is also a lot of humor in the book, particularly in how you describe the culture of Berkeley.

I'm glad there was humor in there. I don't think we could have taken all the really heavy scenes without some humor mixed in. The humor is just me pointing out things that are real about living in Berkeley. Berkeley has this hyper-conscious, social justice-y feel mixed with this very luxurious way of living. It’s a way of life in which people look for the best of the best, whether it’s in their scones or in their childcare. Inherently that is a set up for failure. At some point, we've all tried that quest for the best of something and failed. I think that's funny.

Lucky Boy feels like a more ambitious book than your first novel, The Prayer Room. What were some of the lessons you learned writing your first book that helped you to write Lucky Boy?

From The Prayer Room, I learned that digging deep and telling a story for its characters is much more important than having a beautifully inspired sentence. I became more adept at pulling away the frippery and getting down into character and into story. I also gained stamina. Writing takes a lot of mental and even physical stamina. It took years to build that up so I was able to write big meaty chapters that really got into the heart of where I was trying to go.

One of the things that feels so ambitious about Lucky Boy is how ambiguous it is. I don't know if I should root for Soli or Kavya.

Soli is our hero, but I didn't want there to be a bad guy in this book. People who take in children can't be classified as bad guys. They're loving people. They have good intentions. In my novel, their good intentions create a lot of difficulty, but I could never see Kavya and her husband as anything but good people.

In the time between The Prayer Room and Lucky Boy, you yourself became a mother. Did that change you as a writer?

Becoming a mother influenced my writing a lot, logistically and philosophically. Logistically, I had a lot less time to poodle around in a café letting wonderful things come to me from the muse or whatever. I had to really buckle down and figure out when I was going to write.

When you're a parent, you engage more deeply with the world on an emotional level. Your sympathies get a lot sharper. Also kids just love storytelling. Your child's eyes are fixated on you and they are hanging on every word you say. As a writer, I found it very satisfying to start and finish a story, which I don't often get to do on the page. When I make up stories for my children, I try to put in little morals. For a mother, storytelling is intimacy and agency. As parents we have the power to tell our children the story of the world, to give them the version of the world that we want to give them.

What kind of story about the world do you hope Lucky Boy will tell your children when they are old enough to read it?

What I want my children to take away from Lucky Boy is the idea that you can give of yourself to people in ways you never imagined. I want them to learn emotional generosity. I also want them to take away the theme of perseverance, growth, and renewal. I want them to learn about finding new versions of yourself. When things get really difficult, there is always a new version of yourself you can pull out and try on if you need to.

What was the inspiration for Lucky Boy?

I heard a news story about a Guatemalan woman battling for her son. She was in detention and waiting to be deported. An American couple had been caring for her son while she was incarcerated and wanted to adopt him. I really wanted to know what was going on in these people's minds. What was the biological mother going through? What was the adoptive couple telling themselves? What stage of love had they gotten to that they could justify adopting another woman's child?

In your book, the foster parents are the children of immigrants. Their parents came to the United States legally from India. Why was it important to the story that the foster parents be Indian American?

I am the daughter of immigrants, so writing about Indian Americans is the truest expression of myself. I've always been aware of disparities between groups of immigrants. The difference is that documented immigrants have a visa, which is a privilege, psychologically and legally. But undocumented immigrants have the same hopes, ambitions, and needs as documented immigrants.

I was able to explore those differences because I made Kavya and her husband Indian American. By having the foster couple be Indian American, it makes it clear that this book isn’t about Mexicans versus white people. It’s a book about the different experiences of immigrants.

Was it a challenge to write the character of Soli, whose cultural background and life experience is so different than your own?

That was pretty daunting. I started with research to get a sense of the statistics related to undocumented immigrants in detention. Then I started writing from her point-of-view to force myself to plunge into her experience completely. I eventually switched to the third person, but I used the first person initially to discover where we connected and where we diverged. I will never be her. I will never truly know what it is like to be undocumented. However, there are connections between the two of us: living in Berkeley, being a woman, being a mother—motherhood was a big connection.

My main goal was to present Soli simply as a human being. She is a woman who has hopes for herself and for her little boy. She wants to establish a life for herself, a way to function, work, and be okay. When people start seeing undocumented immigrants as humans, just like any 4th- of 5th- generation American, it becomes harder to see them as criminals and interlopers and easier to see that maybe they do deserve a chance here.

There are some pretty harrowing moments with Soli inside detention facilities. How did you write those scenes?

Again, I started with research. I researched into the detention system so I would know realistically what does and doesn't happen inside those facilities. I learned the very dry step-by-step process an undocumented immigrant goes through from incarceration to deportation. Then I thought a lot about the psychology of incarceration, both from the point of view of people who are imprisoned and those who are in charge. I thought about power dynamics between humans. Then I just tried to engage with the story and tell it in a way that was very spare. I wanted to let the events speak for themselves so that I didn't have to provide commentary on what was happening. The research really empowered me to tell the story that I wanted.

Those scenes are intense, but there is also a lot of humor in the book, particularly in how you describe the culture of Berkeley.

I'm glad there was humor in there. I don't think we could have taken all the really heavy scenes without some humor mixed in. The humor is just me pointing out things that are real about living in Berkeley. Berkeley has this hyper-conscious, social justice-y feel mixed with this very luxurious way of living. It’s a way of life in which people look for the best of the best, whether it’s in their scones or in their childcare. Inherently that is a set up for failure. At some point, we've all tried that quest for the best of something and failed. I think that's funny.

Lucky Boy feels like a more ambitious book than your first novel, The Prayer Room. What were some of the lessons you learned writing your first book that helped you to write Lucky Boy?

From The Prayer Room, I learned that digging deep and telling a story for its characters is much more important than having a beautifully inspired sentence. I became more adept at pulling away the frippery and getting down into character and into story. I also gained stamina. Writing takes a lot of mental and even physical stamina. It took years to build that up so I was able to write big meaty chapters that really got into the heart of where I was trying to go.

One of the things that feels so ambitious about Lucky Boy is how ambiguous it is. I don't know if I should root for Soli or Kavya.

Soli is our hero, but I didn't want there to be a bad guy in this book. People who take in children can't be classified as bad guys. They're loving people. They have good intentions. In my novel, their good intentions create a lot of difficulty, but I could never see Kavya and her husband as anything but good people.

In the time between The Prayer Room and Lucky Boy, you yourself became a mother. Did that change you as a writer?

Becoming a mother influenced my writing a lot, logistically and philosophically. Logistically, I had a lot less time to poodle around in a café letting wonderful things come to me from the muse or whatever. I had to really buckle down and figure out when I was going to write.

When you're a parent, you engage more deeply with the world on an emotional level. Your sympathies get a lot sharper. Also kids just love storytelling. Your child's eyes are fixated on you and they are hanging on every word you say. As a writer, I found it very satisfying to start and finish a story, which I don't often get to do on the page. When I make up stories for my children, I try to put in little morals. For a mother, storytelling is intimacy and agency. As parents we have the power to tell our children the story of the world, to give them the version of the world that we want to give them.

What kind of story about the world do you hope Lucky Boy will tell your children when they are old enough to read it?

What I want my children to take away from Lucky Boy is the idea that you can give of yourself to people in ways you never imagined. I want them to learn emotional generosity. I also want them to take away the theme of perseverance, growth, and renewal. I want them to learn about finding new versions of yourself. When things get really difficult, there is always a new version of yourself you can pull out and try on if you need to.